There is a saying among analysts that correlation is not causation. Chances are, you might have heard this before in a statistics or science course. Yet many professionals continue to misunderstanding these two concepts and how they differ. So let’s clear up any confusion once and for all.

What Is Correlation?

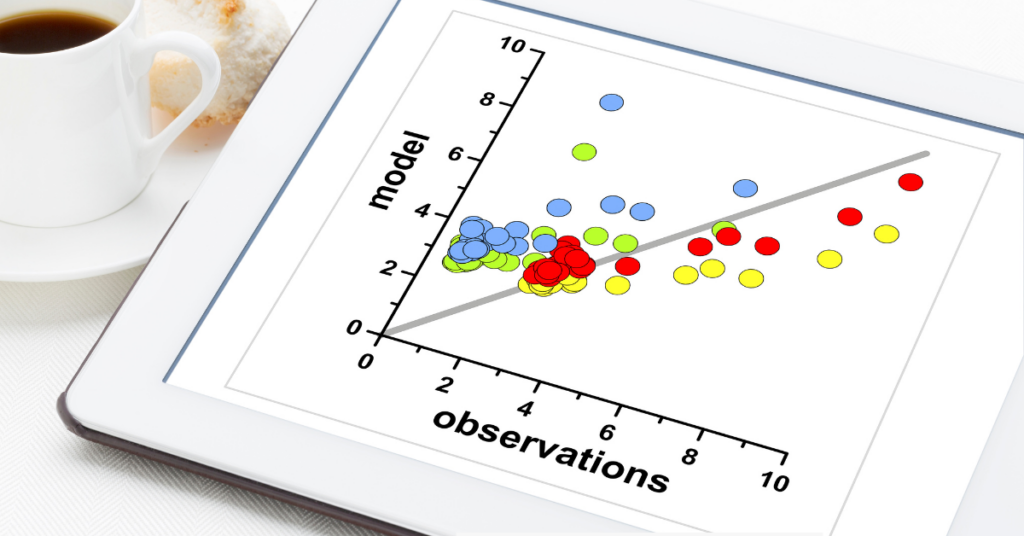

To put it simply, a correlation is relationship between two metrics. When two metrics are correlated, a change in one typically corresponds to a change in the other.

A positive correlation means the two metrics tend to change in the same direction, while a negative correlation means they tend to change in opposite directions.

The size of the correlation measures how strong the relationship is. A correlation of zero (0) indicates there is no relationship. In contrast, a correlation of +/- one (1) indicates the two metrics always change together.

Correlation is an incredibly important concept in analytics. After all, we frequently want to know how different things in our world are related to one another.

Unfortunately, correlation is not causation. Just because two metrics a related doesn’t mean one is causing the other.

What is Causation?

Causation is a special kind of relationship in which one event produces another event with some degree of certainty. When two metrics are causally related, they don’t just change with each other over time. They are inextricably linked.

If you know which is the causal factor, you can create or trigger the effect by simply manipulating the cause.

For consumers of information, however, identifying a causal relationship is not as easy as identifying a correlation. There are three elements that must be present to establish causation between two metrics.

Time Order

This is a matter of simple logic. A cause cannot occur after the effect it produces.

Your car doesn’t move from one location to another, followed by you pressing the gas pedal. The order of events goes the other way: gas pedal, then motion.

Even when the cause and effect appear simultaneous, a close examination will reveal one event happens first.

When you flip a light switch, the light bulb immediately turns on. While these two events appear simultaneous, there is a more complex sequence of causal events happening. The switch closes an electrical circuit that allows electricity to flow to the bulb, causing it to light up.

Correlation

Correlation is another matter of logic in identifying causation. If one event causes another, then the two must be related.

The correlation between cause and effect is the same kind as that described above. We won’t rehash the concept here.

Nonspuriousness

The third factor you must have to establish a causal relationship is nonspuriousness. This rather unpleasant-looking word is jargon for saying that there isn’t a third factor (called a confounder) influencing your proposed cause and effect.

For example, there is a correlation between ice cream sales and homicide. When ice cream sales increase, so does the homicide rate.

Of course, no one believes that people who purchase ice cream are more prone to killing others. Although, I might get a bit testy if someone takes the last of the mint chocolate chip.

The rational explanation of the relationship between ice cream sales and homicide is the weather. In warmer weather, ice cream sales increase; but so does social interaction.

People have more picnics, more parties, more gatherings where to enjoy each other’s company. Unfortunately, this also increase the chance that some people will have disagreements; some of which turn violent.

This is an example of a spurious relationship in which the temperature is a causal factor for both ice cream sales and homicide.

To establish a causal relationship between two events, you’ll need to confirm that there isn’t a spurious third factor. This is often the hardest aspect of establishing causal relationships given the sheer number of factors that one could consider.

Conclusion

Correlation is not causation, but it is an important element in establishing a causal relationship. The next time someone tries to convince you a correlation in their data is evidence of causation you’ll be prepared. Assuming the time ordering of events is correct, you’ll want to know whether they examined potentially spurious factors. Fortunately, proper research design can help eliminate the potential for confounders in an analysis. We’ll explore that in another article.